Finding good employees has been a problem for decades in this industry. In periods of economic boom, finding enough employees can prove to be a challenge. With the industry now settling into a nice growth pattern, this decades-old dilemma could become an even bigger problem over the next 10 years.

Just look at what some Green Industry Pros readers had to say when responding to our fall 2014 survey question: What are the biggest challenges you are facing as a landscape contractor or equipment dealer?

"We are in a growth trend, but are unable to hire enough qualified employees to produce the work so we aren't always eight weeks out," one design/build contractor said. "Clients don't want to wait that long once they make a decision."

"It is difficult to find qualified people," said one equipment dealer. "We recently made two job offers that went south because of criminal background and/or drug testing results. We need healthy, intelligent, self-motivated people who are willing to put in a day of work."

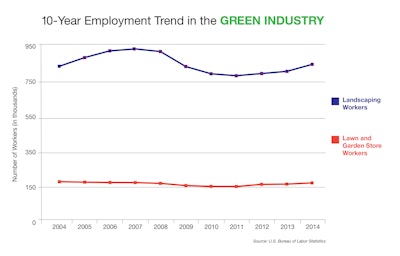

The challenge for landscape companies and equipment dealers is twofold. On the one hand, the need for workers in this industry is back on the upswing after bottoming out in 2011 (see chart). Secondly, many occupations—vocational or otherwise—are also feeling the worker pinch. All of this, arguably, creates more demand for good workers than there is supply.

For example, as one landscape contractor said in response to our fall 2014 survey, "Finding reliable local employees seems to be a growing problem. The mining industry here takes most available employees."

Mitch Nerby of Greg's Lawn Care & Snow Removal in Grand Forks, ND (profiled in our January issue), is dealing with a similar scenario. His company has seen explosive growth over the past few years, and he's struggling to find enough employees to keep up with that growth. "A lot of people want to head to the western part of the state for $30/hour jobs in the oil fields," Nerby relates.

"Hiring good, long-term employees is a real problem," another contractor said. "If the market could bear a 20% price increase, we could afford to offer more benefits. But unfortunately, it can't."

Two types of workers, two sets of issues

It's important to note that there are two components to this industry's worker-shortage issue. Some companies struggle to find trained, skilled employees to serve as crew foremen and managers. Other companies struggle to find entry-level laborers. Many struggle to find both.

"Finding skilled employees and people who can be leaders for us is a constant struggle," says Carlton Tyndall of Atlantic Coast Landscape Company in New Bern, NC. "Finding entry-level workers, on the other hand, seems to go up and down. We can find them by the dozens when business is slow, but when we're busy it always seems like it's a struggle to find extra help. This year has been a lot better for some reason. It might be because people see how our company is growing, so we're getting some applicants who've worked at other landscape companies. We were busy—and hiring—in February already."

"Right now, our struggle in finding qualified employees comes more from the general labor to crew foreman level," says Devon Stanley, maintenance division manager for Benchmark Landscape Construction in Plain City, OH. "There are many management-type personnel out there, but the skilled, or even moderately skilled laborer types are harder to come by for many reasons—most stemming from individuals themselves keeping their employability status in good standing (i.e. clean driving records, good references, etc.)."

Youth gone wild?

Whether you're talking about entry-level employees or trained management types, there is a growing concern that today's younger generation just isn't interested in this industry.

"I cannot find equipment mechanics," one dealer said. "No young people around here want to learn by getting their hands dirty."

"I'm struggling to understand the millennial mindset; lazy, entitled and Americanized," a landscape contractor shared. "Now I'm seeing a trend in our local Latino population where they are even becoming Americanized, particularly in the last couple of years. This is the greatest challenge we are dealing with."

"Our biggest challenge is the pathetic work ethic workers have today," another contractor said. "With little to no Hispanic workforce in our area, the ability to find employees who want to work every day is next to impossible. We see no end in sight to this problem. We have more business than we can handle. We're actually thinking about just reducing staff and raising prices."

Harsh words from a handful of green industry business owners. But it's a sentiment shared by more than just a handful. According to a Green Industry Pros survey conducted in 2011—when the need for employees was considerably smaller than it is today—24% of readers said they couldn't find good employees because American workers are just too lazy. That's double the number who said American workers are simply not aware of the career opportunities in this industry.

Swaying students

Nonetheless, awareness is definitely an issue that has been mounting over the past decade. Generally speaking, enrollment in college landscape, horticulture and small engine-related programs has been on the decline. High school programs are under constant budgetary pressure. The industry has taken notice, and is now taking steps to do what it can to reverse this trend. There have definitely been some glimmers of hope.

Zach Johnson, associate professor of Landscape Business and Landscape Design & Contracting at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, CO, says enrollment in his programs has been steadily climbing since 2008. "We hope to be back to pre-2008 numbers in the next year or two," Johnson says. Enrollment had slipped, Johnson points out, because students were hesitant to pursue careers in a depressed industry where job prospects were dim. It's obviously a different story today.

"We're a relatively new program, only eight years old," shares Frits Rizor, landscape management coordinating instructor at Hocking College in Nelsonville, OH. "I've had around 16 to 20 students a semester. We obviously want to get bigger; I'd love to get up toward that 50-student level. One challenge has been retention; we have had quite a few students drop off from the first to second year. One thing we're trying to do is integrate more hands-on learning earlier in the program to really give students a taste of what they'd be doing with a career in landscaping."

On a positive note, Rizor says the quality of his students has improved markedly. It's all about attracting the right kids in the first place. "We're reaching out more to high school career programs, though there seems to be fewer and fewer of them," Rizor says. "We look at all the high schools in our area. I'll normally contact the instructor, asking if we can visit them to do a presentation one day. It's not just landscaping-related programs either; it can also work for high school agriculture programs."

Industry employers such as landscape companies and equipment dealerships can also play a role in helping to stoke interest in landscaping industry careers. "I love it when professionals want to be part of our advisory boards and really help steer the instruction we're providing," Rizor says.

"I'm very active with three different career/technology centers in the central Ohio region," Stanley relates. "Each is experiencing recruitment challenges. One instructor in particular, though, is starting to have some success in gaining interest from high school students."

Stanley says things like local and/or national skills competitions (such as SkillsUSA and Student Career Days), and field trips to sports turf stadiums, golf courses, cemeteries and other horticulture-related sites can help build a teenager's interest in landscaping. "This particular instructor also has industry representatives such as myself come into the school to provide hands-on training to back up what some of the textbook instruction provides," Stanley adds.

Donna Riddle is feeling pretty good about her horticulture program at Wilkes Community College in Wilkesboro, NC. "We saw a jump in enrollment several years ago," Riddle says. "It was primarily mature students who'd been laid off from manufacturing jobs. Our numbers aren't as high today, but we had our first big group of 18- to 20-year-olds, which was really refreshing. This group has been energetic, innovative, and out-of-the-box thinkers."

Riddle is especially optimistic about the future of her program. An initiative in North Carolina called Career & College Promise allows eligible high school students to begin earning college credit at a community college campus at no cost. "This will give our program a lot more visibility in high schools, while also making it a lot easier on the students," Riddle says.

"We also provide tours to all sophomores from all four high schools in our county," Riddle adds. "We're fortunate to have received a lot of support. We have great facilities and great equipment. When people see that and realize what we have to offer, it really helps solidify things and draw a lot more interest in our program."

The primary intent of initiatives such as Career & College promise is to make post-secondary education more affordable to high school students. Affordability—relative to the wage a landscaping student can expect to earn upon graduation—is at the heart of the issue.

"Students are reluctant to borrow large amounts of money to enter a profession where some employers (landscape companies) don't have a basic understanding of the business and finance," Johnson explains. "These companies give our industry a black eye and further promulgate the perception of low-skillset, low-paid employees."

This same challenge/frustration exists for instructors of small engine repair-related programs. "There is such a need for technicians in outdoor power equipment," says Dan Hein, an instructor at Madison College in Madison, WI. "One challenge is the money some dealerships want to pay these new recruits. If a kid is going to go to school to get the training and skills, and then be offered a $9/hour job, that just isn't going to work. When dealers call me and say they're looking for a technician they want to pay $9/hour, I almost want to hang up on them."

While naturally important, the money one can expect to earn isn't the only thing that will attract a young person to a career in this industry. The work must also be interesting and rewarding. "Many of my students are surprised to see how landscaping and horticulture is a lot more involved than they'd thought," Riddle shares. "They find out that we're scientists and business managers. That kind of variety and opportunity seems to excite them."

"The traditional carbureted engine ... it just isn't sexy enough for today's younger people," Hein says. "Motorcycles are 'cool' so that's what most of my students are initially interested in. Nobody wants to manually tweak a carburetor; they want to plug an engine into a laptop and modify things. There is some great technology coming into outdoor power equipment now, such as electronic fuel-injected engines from Kohler and now Briggs & Stratton. Stihl's M-Tronic technology and Husqvarna's AutoTune is amazing. Working on small engines is getting a lot more interesting, and that's important."

Young and impressionable

Hein is a member of the Equipment & Engine Training Council (EETC), an organization created in 1998 to help address the shortage of equipment service technicians in the outdoor power equipment industry. At its recent annual conference in April, the EETC outlined some initiatives to help encourage more high school students to pursue careers in small engine repair.

Growing technicians state by state. The EETC Board approved an initiative to appoint "state directors". These would be EETC member volunteers who would serve as liaisons to colleges and high schools, and FFA and SkillsUSA organizations within each state. This kind of grassroots outreach, state by state, is designed to help keep the EETC—and small engine repair in general—in front of both educators and students, while also providing invaluable assistance to educators looking to build up their small engine-related programs.

On that note, EETC is also rolling out a new program specifically designed for high schools. "First Step to Power - Small Engine Technology" has two primary objectives: 1) enhance EETC brand recognition among high schools, 2) equip high school and perhaps even junior high school students with just a basic understanding of two- and four-stroke engine theory and preventive maintenance, better laying the groundwork for continued pursuit of a career in small engine repair. First Step to Power is ideal for those schools that simply do not have the resources nor budget to offer a full-blown small engine program.

Changing perceptions of a landscaping career. The National Association of Landscape Professionals (formerly PLANET), through its scholarship program and annual Student Career Days event, has primarily been focused on college students. The NALP Foundation will continue to raise money to provide scholarships, but is also expanding its charter to attract new professional candidates to the industry through public education.

"The Foundation is in the research and development stage when it comes to helping attract students into a career in the landscape industry," says Lisa Schaumann, NALP's director of public relations. "This new mission was developed last year, and the Foundation has to raise the funding to tackle that mission."

Landscape contractor Miles Kuperus Jr., CEO of Farmside Landscape & Design in Sussex, NJ, is the Foundation's incoming president. He says the first step is to get a handle on the root cause of young people's waning interest in landscaping industry careers. That requires research first, and message formulation second.

"We have to identify what makes our industry special so we can make it a very clear career choice," Kuperus says. "Once we get that message clarified, it's going to take many people to beat the drum. But before that we need a clear objective; we're hoping to have that by the end of this year or early next year."

On the topic of beating the drum, NALP, like the EETC, recognizes the importance of drilling down to the state level. "We recognize huge value in working with state landscape associations to get the message out there," Kuperus says. "They are a critical partner in our grassroots efforts, so we need everybody to buy-in and understand what the industry's needs are."

Schaumann says that high schools and high school students will be a primary target of that grassroots outreach, but securing a trained and reliable workforce isn't just about them. "We're also looking at second-career adults, and also military veterans," Schaumann cites as examples.

Regardless of where the workers come from, the point is that they need to come from somewhere. It's up to the industry to do what it can to help attract them.

"There definitely needs to be an initiative to talk directly with high schools and community and technical colleges," Kuperus says. "But more importantly, I think we need to be moving the industry more toward certification, uniformed employees, and all of those things that help us put a more professional package together. The more our industry becomes attractive, the more likely we'll finally get the respect we deserve. That professionalism becomes a magnet.

"The next phase," Kuperus continues, "would be to go to educational institutions and show them what we have to offer in terms of a real profession and real opportunity. I think our best days are ahead of us, with people becoming more grounded in the earth in ways we've never experienced before. So how we go forward is the most important thing. We can talk about the 'now' and make it a negative, or we can talk about the future and attracting more people to be part of that special dream we paint."

The industry is starting to talk about that future, and that's a good thing.

![Doosan Bobcat Wacker Neuson Stack 2ec Js Pb V6e[1]](https://img.greenindustrypros.com/mindful/acbm/workspaces/default/uploads/2025/12/doosan-bobcat-wacker-neuson-stack2ecjspbv6e1.CPyyz8ubHn.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&bg=fff&fill-color=fff&fit=fill&h=100&q=70&w=100)

![Doosan Bobcat Wacker Neuson Stack 2ec Js Pb V6e[1]](https://img.greenindustrypros.com/mindful/acbm/workspaces/default/uploads/2025/12/doosan-bobcat-wacker-neuson-stack2ecjspbv6e1.CPyyz8ubHn.png?ar=16%3A9&auto=format%2Ccompress&bg=fff&fill-color=fff&fit=fill&h=135&q=70&w=240)